What is it and how does it affect wine?

You may already be aware of the term terroir, eluded to in flowery prose as if it’s some flighty, whimsical spirit or indefinable entity inhabiting the soil of a vineyard and thought, “yes, that sounds like nonsense”.

I don’t blame you. We have no word for terroir in English and it is often hard to comprehend. Also, the French are mad. As a Francophile I feel comfortable in asserting this. Their country is beautiful, they’re deliciously un-PC and their cuisine is the best in world. But they are bonkers.

As a dour, joyless Anglo-Saxon, I believe everything can be explained through science and wine is no different. It’s deliberately cloaked in mystery by winemakers and marketers – most likely trying to protect their intellectual property by giving the impression their product cannot be replicated due to an ethereal je ne sais pas we English couldn’t possibly hope to understand – just take our word for it and give us the cash.

The truth is, terroir is very real, routed in science – and it matters. Your garden has terroir and if parts of it receive different hours of sunlight, have different gradients or deeper soil then it has multiple terroirs. If you plant broad beans in all those different spots they will grow and ripen differently because of the different conditions.

The best way to think of terroir is as the sum of environmental factors affecting any given site. Here we will break these down into three factors: soil, climate, and topography.

Soil

Soil is, obviously, critical to the growth of vines. There’s a lot of nonsense spouted about it. I once attended a tasting of Mosel Rieslings in London with a winemaker whose vines grow in slate based soils. He went on to explain how one wine in particular tasted of slate because of this. Slate isn’t water soluble so this isn’t possible. I didn’t challenge him, mainly because I’m unwilling to climb onto my roof, pull off a tile and eat it to see what slate actually tastes like. It did taste of petrol though, presumably because the vineyard is opposite a service station.

So why is soil so important? It’s all to do with hydrology – the relationship between the soil and water. What winegrowers need is a soil which regulates the supply of water to the vine’s roots. Too much water and the vine thinks all is well, kicks back and grows its leaves and shoots at the expense of fruit. No need to ripen my grapes – what’s the hurry? And if left unchecked by human intervention the problem only gets worse as the canopy becomes overgrown and the resulting shade discourages ripening further.

It’s a mistake to think the more leaves a vine has, the more it is able to photosynthesise sunlight and therefore the riper the grapes. The grapes themselves need to be exposed to sunlight and warmth to encourage ripening. Too much shade, caused by too many leaves on a vine, in turn caused by too much water and the grapes won’t ripen.

Think of vines as lazy teenage boys: left to luxuriate in a comfortable, threat-free environment they will sit around playing Call of Duty in their boxers. You can politely request they mow the lawn but what they need is stress/the risk of physical violence applied (within the parameters of English law) so they get on with it. With vines you do this by planting your vineyard on a soil which ensures they have just enough water (and nutrients) to keep them healthy but not so much they become idle.

Many English wine growing areas are planted on the shelf of chalky clay shared with that of Champagne. The Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier grapes destined for their wines are ideally suited to these well drained soils with a relatively high calcium content (described as calcareous). This soil is special for several reasons, the details of which are lengthy but, in short, its chemical properties result in just the right quantity of nutrients being made available to the roots while improving soil structure and therefore encouraging drainage of excess water. The chalk and clay hang on to the water tightly, rationing out supply to the roots meaning that even during times of drought the vine is sustained and during wet weather, much of the excess water drains away. All this helps to ensure the right balance between leaves and fruit and therefore, hopefully, ripe grapes. But there’s more to it than that…

Climate

It’s best to think of climate as the long-term weather pattern in any given region – for our purposes generally assessed over a 30-year period. It consists of factors such as temperature, rainfall, sunlight, humidity and wind.

Temperature

To most of us, wine growing areas are imagined to be stinking hot and baked by the sun; worked by ruddy-faced Mediterranean types wearing 1980s Marseille FC tops. In reality, the finest expressions of wines made from a particular grape tend to be grown in the absolute coolest climate in which it can reach full ripeness. The average temperature requirement during the growing season (winter conditions don’t really matter) is roughly 16°C – 21°C which seems far too cold, but bear in mind this is an average temperature which takes into account chilly spring and autumn mornings as well as the midday summer sun. Bear in mind it’s possible to rescue a poor summer with a long, warm autumn.

It’s important to consider that certain grapes require more heat and take longer to ripen than others. If you tried to grow a late-ripening grape like Grenache in a relatively cool climate like Burgundy’s they wouldn’t ripen at all. Conversely, planting an early-ripening variety like Pinot Noir in the Southern Rhône would result in overly ripe, simple wine with low acidity.

Ripening doesn’t simply concern sugar, although it is the most important indicator. If the weather is too warm for a particular grape, sugar levels will increase too quickly relative to their development of flavour compounds. When sugar levels reach their apex, acidity falls away. This explains why those cheap Pinot Noirs you buy from supermarkets, almost always from hot regions like Central Valley in California, are so flabby and flavourless.

Temperature is of critical importance at every stage of the growth cycle, affecting when vines start to flower and consequently the establishment of fruit (the flowers turn into grapes) as well as how that fruit ripens. Warmer conditions will cause the vine to flower earlier, produce fruit earlier and therefore allow for a longer growing season, typically with less likelihood of crop wrecking diseases like mildew. Crucially, such conditions also mean faster accumulation of sugars, accelerated loss of acidity and the development of flavour compounds. In climates that are too cool for wine production, flowering will happen too late meaning the growing season will be shorter and the grapes therefore will not ripen.

In order to reach their greatest expression, the important thing is that grape varieties are planted where they will develop slowly but sufficiently, only reaching optimum ripeness late in the growing season. The reason for this revolves around sugar, acidity and flavour compounds. Flavour compounds take time to develop. The cooler the growing temperature (within the limits for a particular variety), the longer the fruit takes to ripen and the more complex the flavours that will find their way into the finished wine. Cool conditions also help to retain acidity, providing freshness and balance. If there is too much heat, the grapes will accumulate sugars too quickly and acidity levels will drop, after which the fruit will start to rot and spoil before reaching its true potential.

When looking at terroir as a concept it’s always perilous to consider variables as monoliths because they’re largely interdependent. Temperature is obviously affected by more than a location’s distance from the equator and here we will look at some of these factors.

Sunlight

It is entirely sensible to associate warm weather with sunny days but these factors aren’t necessarily mutually inclusive. Anyone familiar with the great wines of Australia will appreciate a Hunter Valley Semillon (a sensational hangover cure/breakfast wine), made in a very warm region but one which presents with high acidity, relatively low alcohol and little generosity of flavour (in its youth). This is due to cloud cover. Essentially, vines respire (convert sugar and oxygen into energy for growth) at a faster rate at high temperatures. Meanwhile, rates of photosynthesis (which produces sugar from sunlight) are unaffected and therefore more sunlight hours are needed in order to produce enough sugar to ripen the fruit affectively.

Rainfall and Hail

We all consider England to be a very wet country in terms of rainfall but compared to many coastal wine growing areas it really isn’t too bad. Met Office statistics show average rainfall in Sussex, for example, is around 750mm per year. Considering Champagne and Bordeaux experience between 650mm and 800mm respectively and that regions such as Galicia in North West Spain see up to 1500mm you’d be forgiven for wondering why rainfall is such a problem for English wine growers. In many vintages the issue is when the rain falls. Generally, English wine growing regions suffer the heaviest precipitation during the growing season, including autumn when the grapes are to be harvested.

Heavy rain shortly before and during harvest can have serious repercussions to wine quality and yield. Particularly after periods of dry, hot weather, it can lead to grapes swelling quickly as water is channelled to them through the vine causing the skin to split and disease to take hold. This is another reason why planting on soil such as the chalky limestone found in so many European wine regions is so important. If the soil can drain away the excess rainwater the former problem can be ameliorated. However, even then, the rain water on the berries and vines can often find its way into the wine, diluting the juice complicating the issue of when to harvest further

The risk of hail, whether in spring, summer or autumn presents and even greater threat of damage to the grapes, albeit a less likely one, and can decimate entire crops. If it occurs shortly after fruit-set, vines may be able to compensate by concentrating efforts on ripening the remaining berries although yield will obviously be reduced. If hail strikes once the grapes are ripening however the results can be devastating with broken bunches subject to fermentation and diseases which spread throughout those bunches.

Humidity

High humidity is common in coastal areas in particular. High levels of humidity, generally measured as relative humidity (% RH) is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it encourages fungal diseases which are a constant thorn in the side of winemakers in marginal climates. On the other, there is compelling evidence to suggest high humidity levels can actually increase wine quality by limiting transpiration and therefore the uptake from the soil of chemicals including potassium. This reduction in potassium in particular can promote freshness of aroma and flavour while guarding the juice against the effects of bacteria and oxidation. It’s also worth bearing in mind that potassium is an important contributor to vine and grape growth so there is clearly a balance to be struck.

Wind

Wind can be a blessing or a curse depending on the prevailing conditions during the growing season.

A regular, gentle breeze channelled along coastal ranges often assists with the combatting of fungal diseases such as powdery mildew by reducing humidity levels and drying the canopy. Conversely, strong winds during the growing season can draw heat away from vines which is detrimental to the ripening of grapes in marginal climates.

Even if a site is sheltered from the effects of strong winds due to its positioning, an unexpected storm at the wrong time can still wreak havoc. If a storm brings exceptionally strong winds before the vines have been tucked into the trellising, canes can snap, and with that fruit production is lost. Such freak occurrences often come with little to no warning and the job of tucking in 24,000 vines at a moment’s notice bears huge manpower requirements and costs.

Those in marginal climates who choose to plant in exposed plots may need to contend with such physical damage and reduced photosynthesis brought about by the vines’ natural response to such conditions. When a vine detects excessive movement, the pores on its leaves will close, partially or fully, leading to a reduction in photosynthesis and transpiration. Added to the reduction in heat, this can lead to grapes failing to ripen.

In such scenarios, the only tool in a winemaker’s arsenal is to either construct physical windbreaks or plant a barrier of fast growing trees and shrubs.

Frost

Frost is one of the most destructive weather hazards in viticulture and the cause of sleepless nights for all cool climate winemakers the world over during spring and autumn. It typically occurs on still, dry nights with little or no cloud cover meaning there is no moisture in the air to trap heat, leaving it to escape into the atmosphere resulting in rapid surface cooling. This causes water within the vines’ cells to freeze, expanding at it does so, rupturing the soft tissue leading to extensive damage.

Buds and young green shoots can be completely destroyed by spring frosts and in the autumn it can kill off healthy leaves preventing photosynthesis and the ripening of grapes. In 2021 it is estimated that spring frosts resulted in 30% of France’s crop being lost. It should be noted the shoots which do survive are still capable of producing good fruit and the effects of frosts largely concern yield rather than fruit quality.

It is of particular concern to those in regions such as Champagne, Burgundy and indeed England where production depends on the success of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir which naturally bud early and are therefore particularly prone to frost damage during the spring.

Myriad whacky methods are available to combat the impact of frost but they are often limited in their effectiveness and invariably costly. My personal favourite is to hire helicopters to hover over the vineyard, replacing the icy air at ground level with warmer air from above. It is a practice famously employed in New Zealand’s Marlborough region. As an added bonus, a chopper can even be used as a slightly cheaper alternative to a Dyson Superonic hairdryer in order to dry grapes and vines after rainfall at harvest.

More commonly employed in England are smudge pots. These are little oil fuelled burners placed and lit throughout the vineyard (or in the most frost prone areas) when frost is expected. The heat generated rises creating a convection current, cycling the cold air at ground level with warmer air above. It can be effective but typically requires hundreds if not thousands of burners to be positioned, set up and monitored throughout the night which is a huge undertaking and expensive.

The best method of frost protection is to either relocate to the Mediterranean or plant your vineyard on top of an isolated hill where dense cold air will roll downwards, being replaced with warmer air from above. Where this isn’t possible, planting on a slope has comparable results (see topography, slope below)

Diseases and Pests

Nature provides countless viticultural threats for anyone daring enough to plant a vineyard almost anywhere but the threats are most acute in marginal climates such as those commonly found across Northern Europe. Although birds, deer and various creepy crawlies are a problem and will feed on ripe grapes and other plant material, the chief threat is disease – non-systemic diseases to be precise. These are differentiated from systemic diseases in that they do not permanently infect the vines. For our purposes these are fungal diseases whose spores are ever present almost everywhere, including vineyards.

The chief fungal threat experienced in Northern Europe is powdery mildew. It attacks all green growth including fruit, spreads quickly and can lead to severely reduced yield and wine quality. Unusually for a fungus It isn’t much affected by humidity but loves shade. If vineyards are committed to avoiding the use of fungicidal sprays and so concentrate on ensuring they allow the sunlight and fresh air to reach the grapes through vine positioning and stripping away leaves where they are too thick.

Birds, as well as other animals like deer and insects, are also a constant threat to grapes throughout ripening – particularly during veraison when grapes begin to change colour. This has always been the vine’s purpose; to attract birds to eat the berries and have them spread their seeds. Short of netting the entire vineyards, a costly practice common in New Zealand, there is very little that can be done to limit the damage. Bird scarers such as dollies of birds of prey, scarecrows and even propane gas guns or bangers are common, but while initially effective, the scavengers quickly work out it’s a trick and continue to gorge themselves.

Topography

Here, the term topography refers to the surface features of the land found in and around the vineyard such as slopes and hills. It is critical in influencing the local climate (or mesoclimate) and therefore of great importance to viticulture. We will break it down into the following sections:

Slope and aspect

We have already examined the behaviour of cold air and how it sinks relative to warmer air under frost above and therefore know planting on a sloping site is important in minimising the inherent risks of such a threat.

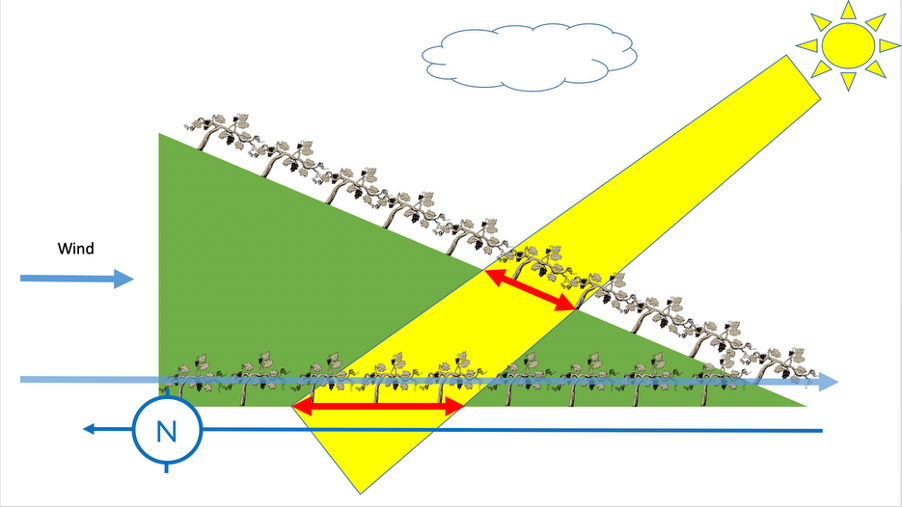

When combined with its aspect (the direction it faces), a slope can have a major effect on the amount of sunlight energy and warmth the vines receive during the growing season. In the Northern Hemisphere, in order to maximise these inputs, winemakers will invariably look to plant vineyards on south facing slopes because they face the sun for longer periods.

South-East facing slopes are generally considered particularly favourable. Because the sun rises in the East, the soil is warmed earlier and that warmth is retained throughout the day and radiated onto the vines for longer.

You may have noticed, having been out in the midday sun without applying sunblock, features like your nose and the top of your cheeks burn more readily than the rest of your face. This is because they’re “sloped” towards the sun. The same principle applies to vineyards. Take a look at the picture below (please, it took me 3 hours on PowerPoint). It shows how the vines on the slope are receiving the same amount of sunlight energy as those on flat ground but over a smaller area. In other words, the sun’s energy is less spread out and therefore more concentrated.

Elevation

You’d be hard-pressed to pick up a half-decent Argentinian Malbec without finding reference to the vineyard’s elevation (often erroneously referred to as “altitude”[1]) on the back label, and with good reason. All things being equal, temperature falls by 0.6°C for every 100m increase in elevation. High elevation therefore allows for the production of fine wine from grapes in areas which would otherwise be far too hot. The most extreme example of this can be found in Salta, Argentina (roughly on the same latitude as Rio de Janeiro) where the Colomé winery plants Malbec at over 3,000m. See our El Provinir “Amauta Absoluto”, from vines planted at over 2,000m

Vineyards with high elevation also receive more UV light which stimulates phenolic synthesis, increasing flavour complexity and intensity as well as colour compounds found in grape skins.

Proximity to Water

Large bodies of water such as lakes and seas cool down and warm up slower than landmasses. They therefore help regulate temperatures throughout the year, avoiding extreme differences in heat between the warmer and cooler months. During those cooler months, waters warm the air and prevailing breezes allowing grapes to reach full ripeness in the Autumn in regions where viticulture would otherwise not be possible. Similarly, damaging spring frosts are made less likely by the warmer conditions at this time of year.

Seas have the added bonus of blessing coastal regions with warm or cool air depending on the different currents they carry. The classic examples are the Gulf Stream which grants north west Europe a climate conducive to viticulture and the Pacific Current which allows for the production of high quality Pinot Noir in areas such as Santa Maria which would otherwise be far too hot.

If you’ve got this far, congratulations. Collect your Cork Dork certificate from your local Institute of Wine and Sprits scholar. If you have any questions about the above or would like to know more, feel free to email me on [email protected]

[1] ‘Altitude’ refers to the distance of a given point above the earth’s surface whereas that points ‘elevation’ refers to its height above sea-level.