Wines are often labelled as “Old Vine”, or “Vielles Vignes” in French, “Alte Reben” in German and so on, but generally with very little, if any, explanation as to what this actually means or why it matters. So what are old vines and do they produce better wines?

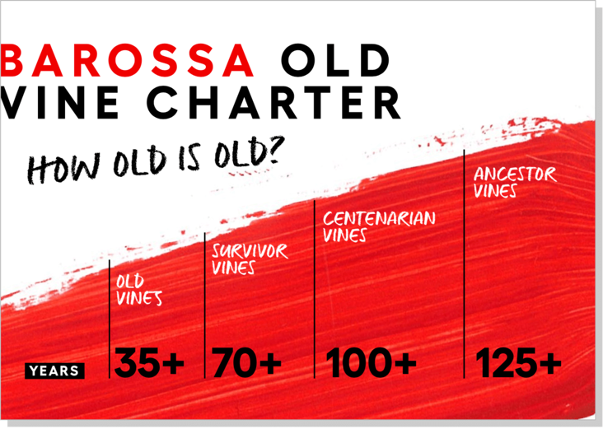

There is no legal definition of what constitutes “Old Vines”. Therefore, any wine could be labelled as such regardless of the average vine age. However, I think South Australia’s “Barossa Old Vine Charter” provides a good rule of thumb which could be applied anywhere:

The minutiae of these categories are beyond the scope of this piece but suffice to say Australia, and South Australia in particular, has a quite enviable inventory of ancient vine material in spite of the ill-conceived vine pull scheme of the 1980s – a program which saw vast swathes of old Australian vineyards ripped up and replaced with more commercially desirable grapes. It was a bit like moving into a Georgian townhouse in the 70s, ripping up the original elm floorboards and replacing them with cork and it must send a shiver down the spine of any Australian wine producer who was alive to see it.

South Australia still boasts the oldest verified commercial vines in the world (still producing wine for sale) at Turkey Flat in Tanunda, Barossa. The vineyard itself is completely unirrigated – one of the reasons for the vines’ longevity. Planted in 1847, the wisened old bush vines have pushed their 170-year-old roots deep into the water table in order to survive. “Irrigated vines grow faster and die younger” says winemaker Mark Bullman. “They’re like pot-plants… turn the water off and they die”. In short, they’re pampered and therefore have not developed a root system to cope with tough conditions. The old vines of Turkey Flat perform best in drier, hotter years; the roots having dug so deep that drought is not a factor. The resultant wine, “The Ancestor”, is only produced in the best vintages and even then in vanishingly small quantities of between 500 and 600 bottles from just 1.1ha. Coupled with fact it is so highly regarded by critics it’s extraordinary the wine “only” costs around £120.

Over the road in neighbouring Eden Valley, you’ll find the home of world renowned Henschke Hill of Grace (planted 1861), a wine second only to Penfold’s Grange as Australia’s red wine icon. It regularly sells between £500-£600 per bottle.

Wines like these act as flagships for the wineries but you can’t base an entire industry around them. Vines this old don’t produce enough fruit to be economically sustainable, especially given the costs of vine management, so most wine needs to come from vines with comparably high yields. As they get older, vines are able to sustain drought better but they are more susceptible to disease and damage and the vineyard manager often finds himself with his work cut out.

In Bordeaux it is common practice, even among many of the grandest Châteaux, to replace vines after 35 years. It must be noted that mature but younger vines between 10 and 30 years of age can produce exceptional fruit too when positioned upon excellent terroir under the management of an expert team.

In spite of how prickly this issue is it is broadly accepted that, all things being equal, older vines make better wine than younger vines do. This can be attributed to two things: the vineyard’s yield and its vigour, both of which are lower in older vines. There are those who believe one is more important than the other and those who believe yield is unimportant but, in essence, old vineyards yield less fruit and are less vigorous. We’ll now look at these two factors in a little detail.

Yield

The term “yield” is used to describe how much fruit (or wine) a vineyard produces – usually expressed as tonnes of fruit per hectare or hectolitres per hectare. Conventional wisdom states lower yields equate to higher quality wine. The Romans were no strangers to this. Someone called Pliny the Elder (AD 23-79), who was presumably unemployed, wrote 37 books for his Emperor Titus on Natural History. Three of those were about wine, the second of which deals extensively with yield and quality. Put very simply (perhaps overly so), the less fruit a vine produces, the riper it is and, consequently, the more concentrated the juice. This is because the same amount of resources (from the earth and sky) are being invested in less product. You can achieve this artificially through methods such as bud rubbing and green harvesting, the latter of which involves cutting any number of nascent bunches from the vine so the ones remaining might better ripen. Imagine you have three children but can only afford to feed two enough food to ensure they are strong enough to work at the mill. Naturally you send the least promising child for medical experiments so the other two may support you in your dotage.

Many wine wonks don’t like this explanation for yields being inversely proportional to wine quality because it’s very hard to prove definitively with science. If you look at a region in isolation, let’s say Bordeaux, you could point to a number of great vintages which resulted from years in which yields were fairly high. Similarly, poor wines are often produced in low yielding vintages. This is usually the result of disease pressure, vine stress and bad weather for example.

Some winemakers in new world countries also protest the causal link between yield and quality and not without reason. A lot of the rules we have created for making great wine are Eurocentric and in some cases a little antiquated. These rules are myriad and largely concern the concept of terroir – best thought of as the total natural environment of any given site. It’s not a load of French twaddle, it’s science – the French just make it sound silly when they start talking about the little pebbles in their vineyards having a soul so everyone listening switches off. Your garden has “terroir”. If you plant sunflowers in part of your garden that doesn’t receive any sun they won’t grow as well as those bathed in light all day. When wine became properly commercialised it followed there would be a necessity for reliable quality and quantity of production. In order to take some of the control for those factors back from mother nature, winemakers and regional bodies invested in scientific research. Personally, I don’t think it follows that yield has nothing to do with quality. You need to look at individual sites, preferably ones which are vinifying the crop of younger vine material separately from the older vines on the same site and look at the resulting juice.

Anyway, what do scientists know? It took them until 2013 to acknowledge dogs wag their tails because they’re happy (seriously, look it up) which everyone else has always known to be the case. The examples of high yielding vineyards producing low quality wines are too numerous to be coincidental. Look at Veneto in North East Italy and compare a true Soave Classico from a low yielding site with the hogwash produced in high yielding vineyards. They are completely different wines: one concentrated, aromatic and full bodied; the other thin, mean and dull. So yield does matter. Whether it is the determining factor in why old vines produce better wine is less clear cut.

Vigour

Vigour is basically the amount of green stuff the vine is producing – leaves and shoots. It is an extremely important factor affecting wine quality. Vines, like any plant need to produce leaves in order to convert sunlight into sugars and so on. But too many leaves will provide too much shade and inhibit grape ripening. The reason for this is rather pleasing. Vines evolved as tree climbers in forests and jungles. Their purpose was to ascend the canopy by concentrating resources on growing their shoots and leaves. Once bathed in sunlight, the vine would switch priorities to ripening fruit in order to attract birds to eat it, fly away and pass out the seeds thereby propagating the plant’s genetic material. That is how vines continued to exist in nature for millions of years and they haven’t changed an awful lot in genetic terms in the intervening years.

As with the finished product, viticulture is about achieving the right balance. Just the right amount of leaves to allow the right amount of fruit to ripen coupled with the right amount of sunlight for any given vineyard. Having an overgrown canopy can also provide conditions (a microclimate) conducive to rot and other diseases which seriously affect quality (and quantity). Sunlight and airflow provided by an open canopy are excellent preventions. Old vines achieve this balance naturally by being less vigorous, providing relatively open canopies without the need for intensive and skilled intervention from vineyard workers. But human interference is risky because if it isn’t done at the perfect time, the vine will compensate by increasing the size of the remaining grapes which will result in reduced concentration. Old vines do the work for you.

Interestingly, it is also often observed that very young vines can produce fruit every bit as good as old vines. During the legendary “Judgement of Paris” of 1976, in which Californian Cabernet Sauvignons and Chardonnays were assessed against the best equivalents from Bordeaux and Burgundy, Stag’s Leap SLV Cab Sauv came out on top in the red category. This was the first ever bottling of SLV, produced from three year old vines. While this is remarkable for many reasons, it was almost certainly, in large part, due to vine age. Very juvenile vines have similarly low vigour and yields. As they establish themselves yields and vigour increase and the vineyard manager must micromanage them to ensure the vines attain balance.

Old vine wines are typically expensive due to their high quality, and therefore demand, and their low supply. But this isn’t always the case. Vine Wine has a number of very reasonably priced wines produced from the fruit of very old vine material. Below are some of our favourites:

Strange Kompanjie Old Vine Palomino, Piekenierskloof, South Africa – £11.50

From gnarled, stumpy old vines on the fecund plateau of Piekenierskloof. Fresh and zesty with notes of almond skin, fennel and a hint of jasmine. A bright, natural acidity on the palate is complemented by fennel, almond nuttiness and the residual salinity of a dry-grown vineyard. The vines meagre yield gives a wine that’s concentrated, bright, textural and distinctly salty on the finish.

Lone Palm Vineyards Old Vine Grenache, Barossa Valley, Australia – £16.50

Sourced from three venerable vineyards all over 80-90 years old. Fresh, black cherry and raspberry juice with heady, sweet cinnamon and clove on the nose. This follows on the palate which is soft and rich yet very bright with some gorgeous savoury notes on the finish.

Percheron Old Vine Cinsault, Coastal Region, South Africa – £9.60

From wisened old Cinsault bush vines, dry farmed on coastal vineyards. Bright, expressive and gently savoury on the nose. On the palate there is fresh pomegranate, game notes, and a core of shining cherry fruit. This is a beautifully defined expression of South Africa’s most fashionable varietal.

Dandelion Vineyards “Lionheart of the Barossa” Shiraz, Barossa, Australia – £15.75

Inky purple in colour, this wine opens with intense notes of blackberry jam, rosemary, chocolate, plums and black olive. A dash of new oak adds a toasty caramel note. The palate shows great intensity and concentration underpinned by refreshing acidity and fine tannins. The fruit for this wine comes from ancient, ungrafted vines, many over a hundred years of age.